Otherworldly Days and Wild Flights on Southwestern Africa’s Spooky Skeleton Coast

From left, a local tribesman, one of our trusty Land Rovers, and guide Andre Schoeman

#WhereNextDestinations - Guest storyteller Chez Chezak shares his tale of an unforgettable guide, haunting shipwrecks, moaning dunes, and much more in Namibia’s magnificent wastelands.

We were flying low—the little Cessna 210 just a few hundred feet above the crashing Skeleton Coast surf—but we were looking up, at sand dunes towering above us. Though hundreds of feet in the air, we were still, uncannily, flying among the dunes. We could be in only one place on earth: Namibia.

The remarkable desert landscape found in this gem of southwestern Africa stretches across nearly a thousand miles of Atlantic coastline, creating fantastic juxtapositions. Ocean surf crashes into dramatic sand bluffs. Red dunes—some more than 1,000 feet tall—rise starkly against endless blue sky.

And we had it all to ourselves in our little Cessna.

Leylandsdrift Camp

“Exactly the Guy We Want”

Our four-day plane adventure, run by Skeleton Coast Safaris, had begun in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital. The café-size terminal at Eros Airport, the hub for regional domestic flights, teemed with travelers en route to a variety of safari lodges. Dashing young pilots would regularly stroll in from the flight line, call out a name, and then literally fly off with their VIP.

Eventually the crowd thinned and I realized the gentleman sitting next to me was on my trip. Iain worked for a British tour company and was on a scouting mission. We passed the time sharing past adventures and speculating on who our pilot was. Finally, with the waiting room nearly empty, a disheveled 60-year-old man shuffled in, his unkempt mustache nearly obscuring his upper lip, his hair flying wild beneath a cattywampus baseball cap.

“Oh, man, I hope that’s not our guy,” I said.

“No, mate,” replied Iain. “That’s exactly the guy we want. Because that guy has been flying forever.”

The gentleman, veteran guide Andre Schoeman, called out our names, introduced himself, and led us out into the brilliant Namibian sunlight, where his Cessna awaited.

One of the many magical sights seen from our Cessna

Surveying the Ruins

With a bird’s-eye view, we observed the majestic detritus of the coast’s storied past. Over the days, Andre’s expert eye found ancient aircraft hangers, abandoned diamond mines, and the skeletal remains of ships wrecked on the treacherous coast over the past century.

Andre would often bring the aircraft down on what he generously called “landing strips.” There was never any pavement or tarmac, no control tower, not even a windsock, just a flat section of gravel or packed sand that Andre had used hundreds of times before. He’d been flying since his teens, before he earned his driver’s license. He’d flown dozens of combat missions in the South African Border War of 1966–’89 (a.k.a. the Namibian War of Independence).

At night, at tented camps, we would eat dinner by lantern light as Andre poured out his encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s history, native peoples, and wildlife.

A Skeleton Coast shipwreck

A Few Tricks Up the Old Sleeve

Once on the ground, Andre would often produce tubs of breads, meats, cheeses, potato salad, condiments, cookies, and an array of beverages. We’d make sandwiches and picnic off the tailplane. From there, we’d tromp out to explore a nearby wreck, ruin, or fantastic geological feature. And at every turn, Andre was an absolute font of knowledge, rattling off the Latin names of flora and fauna, describing mining or construction techniques, recounting coastal history and lore, telling his tales of combat missions flown during the war, and detailing the histories of shipwrecks we encountered.

He also proved even more resourceful than expected, with resources stashed here and there, often in the form of a much-loved Land Rover. The first time he magically produced a “Landy,” we were munching the last bites of our picnic lunch and casually chatting about how we wished we could run up some of the imposing dunes arrayed before us.

“So why don’t we then?” asked Andre, who then sauntered off to a dilapidated old hanger and drove a Landy out as we gaped in astonishment. The coughing white beast wasn’t going to win any beauty contests. Her complexion reflected a lifetime exposed to the harsh elements of the Skeleton Coast, her seats belched stuffing, and her tires were pitted and grayed. But she was able, and she was ours. Soon we were bounding joyfully along the dunes, Iain and myself perched on a well-cushioned but delightfully precarious seat bolted to the rooftop luggage rack.

Looking for a gleefully unnerving, gut-twisting, desert-playground roller coaster? Motor up a dune as steep as a double-black-diamond ski run, approach the apex, see nothing but empty sky above, and then drop down the other side. And repeat. Though my brain tried to rationalize it on the sixth, seventh, and eighth such run, I never got used to it. But we laughed like schoolboys every time.

Some of the “singing” Namibian sand, magnified

A Himba girl with her baby sister

Singing Dunes and Gypsy Elephants

The next morning, we flew north along the Skeleton Coast, landing occasionally to explore the most unique aspects of the landscape. At one stop (and via another rustic but capable Landy), we stood atop yet another massive dune face as Andre introduced us to the singing sands. Within a very narrow band, just the right distance from the coast, the sea salt particulates in the air are the perfect size to settle into the sand and create a unique auditory effect.

Though we were skeptical at first, Andre told us to just take a seat and slide down the slope. As we did, the sand around each one of us began to hum. Our weight compressing the sands, they chanted with an unforgettable moan. We were utterly mesmerized by this otherworldly phenomenon. As soon as we reached the bottom of the dune, we’d race back to the top to do it again.

That evening’s camp treated us to sweeping views of the dry Hoarusib Valley and sightings of Namibia’s desert elephant. These elephants are not a distinct subspecies other African elephants but have simply adapted over many generations, taking on family traits that help them better survive in a desert environment. Their broader feet, longer legs, and smaller bodies bespeak their need to walk long distances to water points. These desert gypsies were elusive, staying well away from the camp, but they made their presence known by thrashing among the trees and occasionally calling out with their trumpet-like voices.

View from atop a Land Rover about to plunge down a sky-scraping dune

Galactic Views

After another morning of airborne sightseeing, we landed some distance from a camp along the Kunene River. Wouldn’t you know it, another willing Landy waited nearby. We hopped aboard and drove until the land fell away, revealing endless views across the Kunene Valley and into Angola. Later, with a full stomach, a drink in hand, and a popping fire, we were treated to an IMAX-shaming view of the cloudy, nebulous Milky Way laid out above us. In the complete absence of light pollution, the stars didn’t twinkle; they straight-up flashed. I was sure they were the safety lights of a distant aircraft, and even after Andre politely corrected me, I still had to stare at the night sky for a few minutes to believe what I was seeing.

A Vehicle for Every Occasion

The next morning, Andre surprised us yet again with a powerboat tucked into the camp’s river bank. He then took us on an excursion upriver, pointing out the geologic anomalies along the way, telling us where the gators most often lurked, and allowing us a quick stop to step foot into Angola. We then hopped into this camp’s Landy and puttered out to a small village that the nomadic Himba people were currently calling home. You might be familiar with the Himba from their complex hairstyles and the rust-colored pigment—a mix of butterfat and ochre—that they apply to their skin. We crossed the language barrier with two Himba women for a while—one of whom was terribly scarred across her torso from an old alligator attack—and bought some of their meticulously woven baskets.

Later, as we ascended out of the valley, a problem with the plucky old Landy’s fuel line kept causing her engine to sputter and quit. The steep angle of the terrain was preventing fuel from flowing properly. Andre fidgeted with the engine a bit and then came up with a simple solution. He would reverse the angle of the fuel line by simply driving backwards, so that the engine was lower than the fuel source. We drove in reverse for nearly an hour before topping out onto flatter terrain, turning the Landy back in the proper direction, and finishing the drive to the landing strip. Lamenting the coming end of our adventure, we loaded up the Cessna one more time and flew back to civilization.

My Personal Epic

I’ve been to some 36 countries in my travel career, and I’ve taken three more trips to Namibia since this time. To this day, it’s hard for me to even consider another adventure on par with this trip. None of them has been as unique, as foreign (sometimes alien), as arresting, or as truly fascinating as my first Namibia adventure. Though my bucket list is long, I want to do this particular trip all over again. It’s like driving up and sliding down a massive sand dune: it never gets old.

WORDS & PHOTOS BY CHEZ CHESAK: A travel writer and executive director of the Outdoor Writers Association of America, Chesak and his wife are diligently saving their dollars to someday take their daughters to Namibia.

Chez Chesak

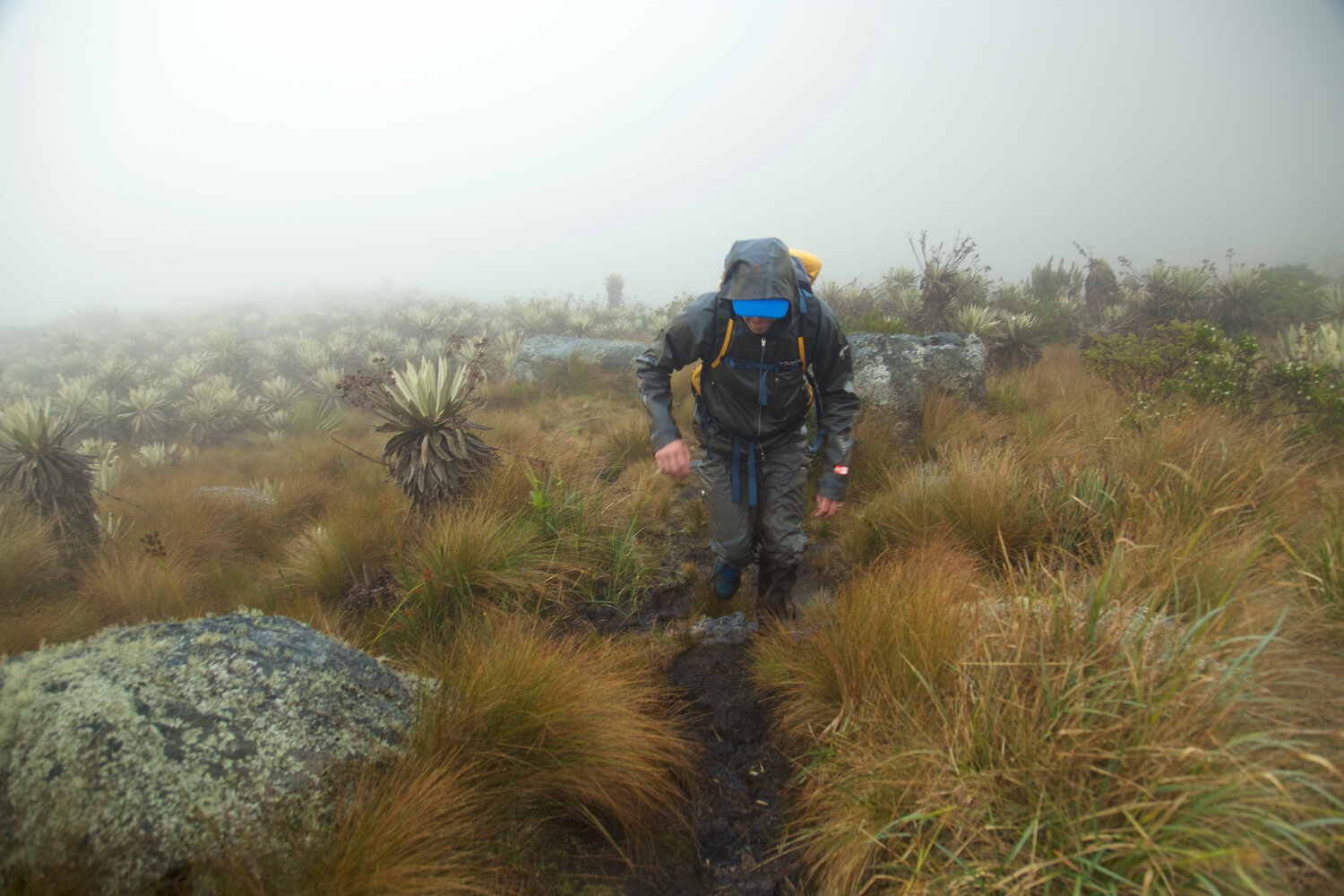

Collaborating with REI Adventures to capture their 10-day Andean trekking expedition.